|

|

GMRS and Amateur

Radio Basic 101 |

|

|

|

Lesson

1 |

|

|

|

What

is the difference between a “channel” and a “frequency?” Frequency

is expressed in hertz (hz), or megahertz (mhz) for 1,000,000 hertz. To

receive a signal that is transmitted, both radios must be on the same

frequency. The FM broadcast radio in your car is a good example.

If you want to listen to a radio station that broadcasts on 105.5 Mhz, then you tune to that frequency. If you do it

a lot, then you might use the preset, so you only have to push one button.

Essentially, you have programmed a “channel” in your radio. On your

television, the manufacturer has programmed the “channels” for you. On

your cable TV box, the cable company programs and reprograms your channels on

the box through the cable. (Don’t you just love it when you like to

watch a program on a cable channel, then you turn it on the next day to find

its now the “golf channel.”) The

“FRS (Family Radio Service)” walkie-talkies you usually see for sale in Home

Depot or Walmart have pre-programmed channels. These are short range

only. (2-4 miles). They don’t require a license, AS LONG AS they

are used within the rules. They will

not have the ability to attach an external antenna. We

can program ham radios and most “GMRS” radios from the keyboard or with a

computer. These can be hand held radios, mobile radios, or base station

radios. In other words, its

like setting up “speed dial” on your telephone. Radios

that can transmit on Ham AND GMRS or FRS (on the same radio) are/were usually

sold on the internet. The FCC has

stopped importation of these to some extent. Why

do we need two different frequencies on one channel? To

use a REPEATER we have to

transmit on one frequency and listen on another aka “duplex”. This is

called an offset. For UHF, its traditionally 5 Mhz. This is

because most repeaters must transmit and receive AT THE SAME TIME.

Frequency separation is necessary to prevent feedback and burning out the

receiver. The good news is that ham radios have this offset preset in

the menu for us, so it’s automatic. Our programming software usually

fills in that blank for us. If we program a channel from the buttons on

the radio, we usually don’t have to worry with it. We don’t need an

offset to talk “simplex,” meaning direct (no repeater). With GMRS

radios, this may be pre-set or may require you to go into a menu to

set. Since

the Chinese have been marketing radios that may be programmed for ham or

GMRS, much of it is not automatic. These radios are more difficult to

set up and there are legal issues. UHF Ham (only) radios usually

can be modified for GMRS, but there are still legal issues. (Kinda like

the CB radio issues.) Newer Chinese radios (Baofeng) are less likely to

work on both, depending on the company importing them. U.S. Customs

apparently has cracked down on the larger importers. You may hear that

this is all in the “no-one-cares” category, but when I fly, I would not carry

a Chinese radio through TSA or Customs. The Japanese brands do not have

import issues. Baofeng is becoming more compliant with FCC rules.

|

|

|

|

Lesson

2 |

|

|

|

What

is “tone” with respect to ham or GMRS radio? On

most ham, GMRS, commercial, or public safety repeaters a subaudible tone must

be transmitted with the signal to trigger the repeater. There are

specific tones (outside of the ability to hear) that can be programmed into

the channel you enter the repeater frequencies in. When you see the

term “memory” in a manual or radio menu, they are referring to the

frequencies, tone, etc. that you have programmed into that “channel.” The

purpose of the tones is to keep interference from keying up the

repeater. (Some repeaters are just two radios tied together with

special circuits.) A

company called RT Systems sells software

and cables for programming MOST ham and some GMRS radios. It’s always

best to learn how to program from the keypad first, but if you reprogram

numerous channels or do it often, the software is the way to go. On a

computer, the software opens something like a spreadsheet to load the data

into. Remember

you can always listen by just entering the listed frequency. You don’t

need to deal with the offset or tone for that. Other

types of tones can be used, such as digital tones, or tones for the receive

AND transmit, but that’s when your further along. If

you hear a constant noise instead of people talking on a frequency, that’s

usually because they are in a digital mode. You won’t be able to listen

on regular FM. Our local repeaters automatically work on either, but if

someone enters the conversation in regular FM, everything will switch to FM

automatically. In some areas you may find repeaters that are NOT

automatic and only operate digital. Only ham repeaters do this.

GMRS repeaters can not operate in digital

modes. There are no FRS repeaters, however both systems share a few

frequencies. There

is a simplex repeater in the area on VHF at 147.420, but you will likely only

hear it south of SR44. You will hear world-wide radio traffic on

it. It is fed into the system from an internet connection to the

repeater. You

CAN listen in on 443.375 Mhz right now. The

local ARES UHF repeater is also connected. Once you get a ham license,

you will be able to transmit on it. The British Girl Scouts were

connected from Wales this morning. They were talking to Bud (W4YEE) in

Beverly Hills. Internet

connections are fed into some repeaters from servers that are called

“Reflectors.” 443.375 is on the “East Coast Reflector.” The connection system between radio and

internet is called “Allstar” if it has the ability to mix different

modes. |

|

|

|

Lesson

3 |

|

|

|

AMATEUR RADIO FREQUENCY CHARTS To learn about the frequency and modes of operation for

each license class, we typically refer to one of the frequency charts

published by the ARRL on their website at:

https://www.arrl.org/graphical-frequency-allocations. The charts can be downloaded

from the webpage in various formats to suit your needs. You will want to print one of these for

your radio area. We typically memorize

some of it by using it so often. There

is usually a test question or two related to frequency information on the

charts. FREQUENCY vs. WAVE LENGTH Since this section involves metric units of measure, you

might want to take a quick look at this quick reference on metric measures. When talking radios, we use the terms frequency

and wavelength often. The terms

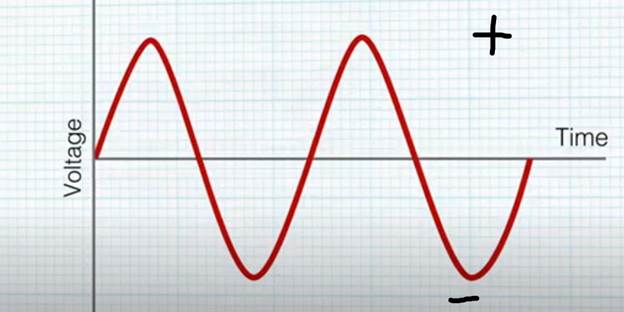

are NOT the same, but they are mathematically related. Radio waves are electromagnetic and radiate

back and forth between negative and positive voltage, just like the power you

get from an electrical outlet at home (alternating current or “A/C”). This type of wave form is a sinusoidal

wave, or sinusoid (symbol: ∿). We usually just call it a “sine wave,”

for short. (Sine is also a

trigonometry function. They are

related, but you won’t need that information for this license.) When we graph a sine wave it looks like an “S” on its

side.

Frequency is the number of

waves in one second. In radio, we use the term megahertz (Mhz) or kilohertz (Khz)

to describe a radio frequency. It

means one million or one thousand hertz. (Hertz was the name of the scientist

that studied this principle.) Hertz

may also be called cycles. Old

radios may have “Mc” or “Kc” on the dial. Wavelength is the measure of

the length of the wave in meters.

(Everything is metric in science.) To

determine wavelength from the frequency, we use the formula: 300 / frequency in mhz = wavelength in meters For instance, our local VHF repeater transmits on 146.955

Mhz. To convert to wavelength: 300 /146.955 = 2.04144126 We just round this off to 2. In amateur radio we call our VHF band “2 meter.” It ranges from 144-148 Mhz. The amateur band in the 420-450 Mhz range works out to about .7 meters. Since .7 meters equals 70 centimeters we usually call it the 70 cm band for

convenience. This is very close to the

GMRS band. When describing a

particular band, we usually calculate from the middle frequency in the band,

then round off. By the way, wavelength tells us how long our antennas

need to be to work properly. (There is

a simple formula for this using inches.) MODES When we refer to “mode” in radio, we are referring to AM

or FM, and others, much like AM and FM on your car stereo. AM is the acronym for amplitude

modulation and FM is the acronym for frequency modulation. The Amateur Radio Technician license allows

the use of amateur radio bands in the VHF (144-148 Mhz)

and UHF 420-450 Mhz range). FM is the usual mode for VHF and UHF. FM is the only allowable mode for

GMRS. Please watch this video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QEubAxBfqKU Other modes a Technician may use

include digital, continuous wave (cw), or single

sideband (SSB) on ham radio. AM is

still used but rarely. There are AM groups

that meet on the air in the shortwave bands weekly. The CW mode is the first mode ever developed for

telegraph and early radio. You may

know it as “morse code.” Turn on your sound, and CLICK FOR CW MESSAGE. There are frequencies in most of the authorized amateur

radio bands reserved for cw use. Morse code

is no longer required for any level of amateur license, but many still enjoy

using it. It is advantageous for low

power and weak signal use. It is

popular for radio contesting in the shortwave bands. There are a variety of digital modes. Some are proprietary and are found as an

option on certain brands and models of radios. Digital modes work like a computer or fax

machine - just a combination of off-and-on at really high speed. CW is very similar, but can be decoded by

just listening. Email and

low-resolution photos can be sent over radio using digital formats. Live television signal may also be

transmitted, however is more of a novelty.

Single sideband (SSB) is the predominant mode used for

voice communications over shortwave bands (3-30 Mhz). It is sometimes used on VHF or UHF when

band conditions meet certain criteria.

SSB is like using half of an AM signal. Its either lower sideband or upper

sideband. It draws less power than AM,

which helps save battery power when portable.

A smaller portion of the band is used, so more operators can operate

within the band. There is less noise

on SSB than am, but more than FM. |

|

|

|

Lesson

4 How

many miles can I transmit with my radio?

Or What’s my range? Well……...

this is going to take a while to explain. Radio

frequencies are usually grouped in “bands.”

This is just a convenient way of grouping frequencies for regulatory, technical,

and practical reasons. We will refer

to “bands” a lot from now on. Amateur

Radio (aka “Ham”) When

we talk about most radio bands, we find the frequency range within a

particular band has similar characteristics with respect to distance,

penetration of objects, and propagation. Ok, here is a new term – propagation. Some radio signals will refract when they

enter the ionosphere. Refraction is

not the same as reflection, but the end result is much the same. This is often called “signal bounce.” The degree to which this works varies by

the frequency, time of day, and space conditions. Radiation from space, like sun light,

alters the degree of ionization of various levels of the atmosphere. As a result, some frequencies refract better

at night than in the daytime and vice versa.

This is why CB radio is so noisy most of the time, especially at

night. If you are old enough, you may

remember listening to the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville on AM broadcast radio

at night. “Shortwave” radio depends on

propagation. “Shortwave” covers

frequencies below 30 mhz to one mhz. Because of propagation, we can usually

communicate around North America during the daytime in the 14.1-14.4 mhz range. It fades

a little after sundown most of the time, and 3.8 – 4 mhz

begins to propagate until daylight and early morning. Lower frequencies tend to curve with the

earth a little. Since we may be

communicating beyond our time zone, it may be good here, but not there, or

vice versa. Like Jimmy Buffett said, “its

5:00 somewhere.” As

it turns out, radio frequencies above 30 megahertz don’t refract often. The higher the frequency, the less likely

it will ever refract, however during foggy conditions we occasionally

experience temporary “tropospheric ducting” on VHF or even UHF. (Think Star Trek “worm holes.”) Ham

radio uses VHF (144 -148 mhz) and UHF (420 - 450 mhz) for local use.

FRS operates around 462 mhz and GMRS

operates around 462 and 467 mhz. The Marine

VHF band is 156 -174 mhz. VHF has been

known to travel hundreds of miles. UHF

may reach 200 miles with normal antennas.

VHF and frequencies above are considered pretty much “line-of-sight”

because they rarely refract or reflect.

As a result of the line-of-sight limitation, the height of your

antenna will usually determine your maximum range for VHF and especially UHF. The line-of-sight will vary a bit from the

radio signal path due to various factors.

Lower frequencies tend to curve a little with the earth, but higher

frequencies curve less. Higher

frequencies will usually penetrate objects and materials better than low

frequencies. For this reason, VHF

works well outside and to a lesser degree inside homes and buildings. Buildings will block VHF signal depending

on the materials. Density, molecular

structure, and moisture content are factors. Metal roofs are difficult to

penetrate, period. Hotel windows and

glass doors are often tinted with metallic substances that block signal to

some degree. More power output usually

helps. UHF penetrates buildings much

better, but is still limited. This is

particularly an issue when using hand held radios. We measure output power in “watts.” For

these reasons, you will find more UHF repeaters in cities with high-rise buildings. A

“base station” or “mobile” radio will usually have an external antenna, so it

will do better and need less power. The

higher the antenna, the more range you will have. This is why radio repeaters are usually

mounted as high as we can get them. In

Florida an antenna at 300 feet on the UHF band can usually cover a 40-mile

radius with 50 watts of power output.

The ground elevation is part of that height. It is usually not possible to penetrate hills

and mountains. Trees affect VHF depending upon their moisture content. When there are no obstacles or hills UHF

will travel a little further on lower power outputs than VHF. Since

the Technician radio license enables a new ham to operate on VHF and UHF, a

handheld radio is often a new ham’s first radio. You can usually expect a four-mile range at

best on flat ground between two hand held radios. Being on top of a hill will extend

that. Plugging into an external

antenna will help a lot. Since hand

held radios rarely emit more than five watts, a mobile radio is much more

useful. They are usually 50-100 watts

and an antenna on a vehicle is a better radiator of signal. “Rubber ducky” antennas don’t have the

benefits of a good ground or “counterpoise”. Despite the advantages of installing a

radio in your vehicle, the range can be expected to be only four to 10 miles

on flat ground without major obstacles.

When contacting a base station radio or repeater, this range extends

dramatically. Just FYI, you can buy a

mobile radio and hook it to a power supply to use it for a base station. A VHF or UHF handheld can transmit about

200 miles to another handheld in an aircraft by a window that is flying at or

over 15,000 feet. (Yep, I’ve done it.)

The curvature of the earth becomes a

factor then. Try

this online calculator: https://www.everythingrf.com/rf-calculators/line-of-sight-calculator. Tip:

A kilometer (km) is about .6 miles.

Get used to metric! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to Home

Page

5/28/2025 5:48:46 PM |

|